Road to independence[edit]

An upper-class emerged in South Carolina and Virginia, with wealth based on large plantations operated by slave labor. A unique class system operated in upstate New York, where Dutch tenant farmers rented land from very wealthy Dutch proprietors, such as the Van Rensselaer family. The other colonies were more egalitarian, with Pennsylvania being representative. By the mid-18th century Pennsylvania was basically a middle-class colony with limited respect for its small upper-class. A writer in the Pennsylvania Journal in 1756 summed it up:

Political integration and autonomy[edit]

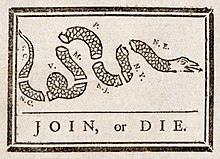

The French and Indian War (1754–63), part of the larger Seven Years' War, was a watershed event in the political development of the colonies. The influence of the French and Native Americans, the main rivals of the British Crown in the colonies and Canada, was significantly reduced and the territory of the Thirteen Colonies expanded into New France, both in Canada and Louisiana. The war effort also resulted in greater political integration of the colonies, as reflected in the Albany Congress and symbolized by Benjamin Franklin's call for the colonies to "Join, or Die". Franklin was a man of many inventions – one of which was the concept of a United States of America, which emerged after 1765 and would be realized a decade later.[37]

Taxation without representation[edit]

Following Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America, King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, with the goal of organizing the new North American empire and protecting the Native Americans from colonial expansion into western lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains. In the following years, strains developed in the relations between the colonists and the Crown. The British Parliament passed the Stamp Act of 1765, imposing a tax on the colonies, without going through the colonial legislatures. The issue was drawn: did Parliament have the right to tax Americans who were not represented in it? Crying "No taxation without representation", the colonists refused to pay the taxes as tensions escalated in the late 1760s and early 1770s.[38]

The Boston Tea Party in 1773 was a direct action by activists in the town of Boston to protest against the new tax on tea. Parliament quickly responded the next year with the Intolerable Acts, stripping Massachusetts of its historic right of self-government and putting it under military rule, which sparked outrage and resistance in all thirteen colonies. Patriot leaders from every colony convened the First Continental Congress to coordinate their resistance to the Intolerable Acts. The Congress called for a boycott of British trade, published a list of rights and grievances, and petitioned the king to rectify those grievances.[39] This appeal to the Crown had no effect, though, and so the Second Continental Congress was convened in 1775 to organize the defense of the colonies against the British Army.

Common people became insurgents against the British even though they were unfamiliar with the ideological rationales being offered. They held very strongly a sense of "rights" that they felt the British were deliberately violating – rights that stressed local autonomy, fair dealing, and government by consent. They were highly sensitive to the issue of tyranny, which they saw manifested by the arrival in Boston of the British Army to punish the Bostonians. This heightened their sense of violated rights, leading to rage and demands for revenge, and they had faith that God was on their side.[40]

American Revolution[edit]

The American Revolutionary War began at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts in April 1775 when the British tried to seize ammunition supplies and arrest the Patriot leaders. In terms of political values, the Americans were largely united on a concept called Republicanism, which rejected aristocracy and emphasized civic duty and a fear of corruption. For the Founding Fathers, according to one team of historians, "republicanism represented more than a particular form of government. It was a way of life, a core ideology, an uncompromising commitment to liberty, and a total rejection of aristocracy."[41]

The Thirteen Colonies began a rebellion against British rule in 1775 and proclaimed their independence in 1776 as the United States of America. In the American Revolutionary War (1775–83) the Americans captured the British invasion army at Saratoga in 1777, secured the Northeast and encouraged the French to make a military alliance with the United States. France brought in Spain and the Netherlands, thus balancing the military and naval forces on each side as Britain had no allies.[42]

George Washington[edit]

General George Washington (1732–99) proved an excellent organizer and administrator who worked successfully with Congress and the state governors, selecting and mentoring his senior officers, supporting and training his troops, and maintaining an idealistic Republican Army. His biggest challenge was logistics, since neither Congress nor the states had the funding to provide adequately for the equipment, munitions, clothing, paychecks, or even the food supply of the soldiers.

As a battlefield tactician, Washington was often outmaneuvered by his British counterparts. As a strategist, however, he had a better idea of how to win the war than they did. The British sent four invasion armies. Washington's strategy forced the first army out of Boston in 1776, and was responsible for the surrender of the second and third armies at Saratoga (1777) and Yorktown (1781). He limited the British control to New York City and a few places while keeping Patriot control of the great majority of the population.[43]

Loyalists and Britain[edit]

The Loyalists, whom the British counted upon heavily, comprised about 20% of the population but suffered weak organization. As the war ended, the final British army sailed out of New York City in November 1783, taking the Loyalist leadership with them. Washington unexpectedly then, instead of seizing power for himself, retired to his farm in Virginia.[43] Political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset observes, "The United States was the first major colony successfully to revolt against colonial rule. In this sense, it was the first 'new nation'."[44]

Declaration of Independence[edit]

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, declared the independence of the colonies by adopting the resolution from Richard Henry Lee, that stated:

No comments:

Post a Comment